Banner by Shirin Kaye

Sick, Sick, Sickle: When Pain Meets Prejudice

by Alexandra Perazzo

Glass shards slice through your veins. The pain is relentless, and every movement sends a wave of agony radiating through your bones. Every breath feels like a battle. You drag yourself to the ER, desperate for relief, only to be told your pain is not that severe, and you must be drug-seeking. A crisis met not with compassion—but suspicion. For thousands of sickle cell warriors, this is reality. A reality shaped not just by disease, but by stigma.

Dr. Lakeya McGill is an assistant professor of medicine, clinical psychologist, and a core faculty member at the Challenges in Managing and Preventing Pain (CHAMPP) Clinical Research Center at the University of Pittsburgh. Her research focuses on examining patient experiences with pain and treatment to uncover key risk factors and therapeutic targets, ultimately improving care for adults with pain and sickle cell disease (SCD). Dr. McGill states, “One of the most common misconceptions about sickle cell warriors is that they are exaggerating their pain, particularly in the emergency department when they are having pain crises, leading to dismissal by healthcare providers and perceptions that patients are ‘drug-seeking.’”

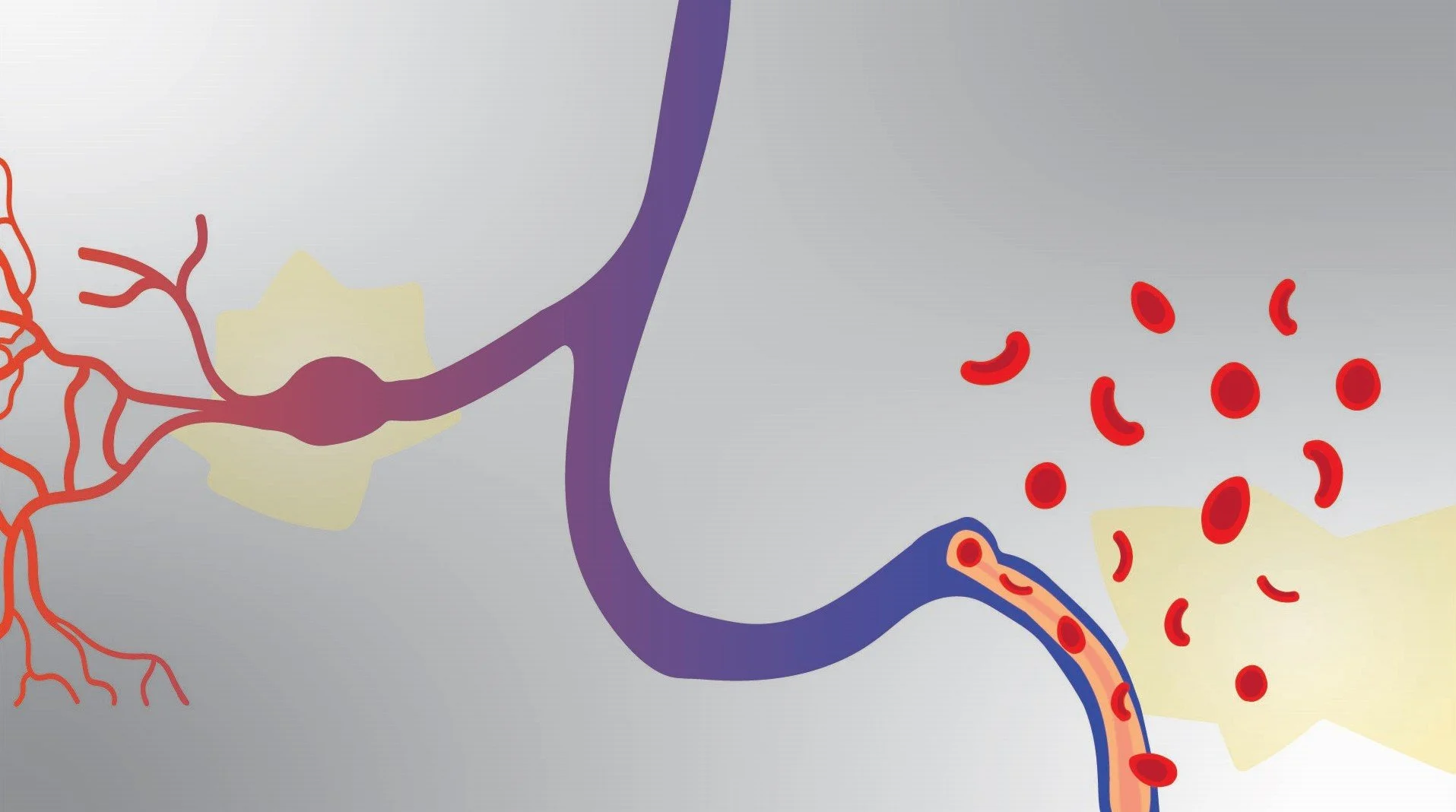

SCD affects more than 100,000 people in the United States and more than 8 million worldwide. The symptoms and health challenges from SCD arise from red blood cells becoming rigid and taking on a sickle shape, leading to early cell death and blockages in small blood vessels. These blockages restrict blood flow and can cause severe complications throughout the body, including anemia, acute and chronic pain, infections, pneumonia, acute chest syndrome, stroke, and organ damage affecting the kidneys, liver, and heart. Because of the complexities and holistic impacts of SCD, Dr. McGill says “there needs to be more education on SCD for clinicians beyond hematologists. SCD complications and comorbidities often require patients to see providers across specialties; this calls for an interdisciplinary approach to treating SCD.”

The complexity of SCD does not only exist in its pathology but also in its history. SCD is more common in Black and Hispanic people, as 90% of those with SCD in the United States are non-Hispanic Black or African American, and 3–9% are Hispanic or Latino. The predominance of SCD in Black and Hispanic populations has an evolutionary history tied to malaria resistance. The sickle cell trait (SCT), where individuals carry one copy of the mutated β-globin hemoglobin gene, provides protection against Plasmodium falciparum, the parasite responsible for the most severe form of malaria. This genetic adaptation arose in regions where malaria was historically widespread, including sub-Saharan Africa, parts of the Middle East, India, and the Mediterranean. Because of this, the sickle cell gene became more prevalent in people from these regions. Therefore, the SCT was advantageous to populations in areas with a high prevalence of maria, causing the gene to flourish. The trait remained common among Black people in the United States due to their ancestral ties to malaria-endemic regions. Hispanic populations, particularly those of Caribbean descent, also have higher rates of SCD due to African and Mediterranean ancestry.

The prevalence of SCD in these groups has halted treating SCD due to ongoing stigma. There are many intersecting forms of stigma faced by warriors, but three central forms include racial stigma, opioid-use stigma, and pain stigma. SCD is a racialized condition, meaning it is laced with systemic racism, misconceptions, and often, inadequate care. Dr. McGill cites that “a study found that patients with SCD experienced longer wait times and delays in receiving pain medication in the emergency department compared to those with other chronic health conditions, as well as compared to Black patients without SCD, highlighting a multifaceted stigma that extends beyond race alone.” Sickle cell warriors often face racial bias, leading to delayed diagnoses and poor pain management, as Dr. McGill explains, “there are disparities in pain outcomes and pain management.” Studies show that Black patients are less likely to receive the same level of pain treatment as white patients, even when reporting similar pain levels. Systemic racism in medicine has contributed to a lack of funding and research for SCD compared to other genetic disorders, such as cystic fibrosis, which predominantly affects white populations. These disparities result in worse health outcomes for people with SCD.

Still, race is not the only contributing factor to the stigma faced by warriors. “It comes down to intersectionality. Sickle cell warriors face stigma beyond race. In Africa there is stigma around SCD, even in predominantly Black populations,” Dr. McGill clarifies. Warriors often rely on opioids for pain relief, but the ongoing opioid crisis has led to increased scrutiny and restricted access to necessary medications. Many doctors hesitate to prescribe opioids, even when patients have a documented history of pain. Opioid stigma can come from many directions, as Dr. McGill further adds, “Patients may be hesitant to take opioids, health care providers may be hesitant to prescribe opioids, and general perceptions around opioids due to the opioid crisis can interfere with patients receiving opioids.” This can result in untreated pain, forcing patients to endure severe crises without adequate medical support. The stigma surrounding opioid use disproportionately harms SCD warriors, who are frequently labeled as drug-seekers rather than individuals in need of medical care.

Pain stigma further exacerbates the challenges faced by SCD warriors, as pain is often invisible and difficult to measure. Many health care providers dismiss or downplay chronic pain, assuming that if a patient is not visibly suffering, their pain must not be severe. Yet, Dr. McGill describes that “research is predominantly focused on addressing acute pain in the emergency department. SCD is complex, as patients experience both acute and chronic pain. The best methods for prescribing and managing pain in warriors are still being studied and refined.” The pain stigma that exists and the lack of knowledge on treating chronic pain in warriors can lead to delayed treatment—forcing patients to repeatedly prove their pain is real. As a result, individuals with SCD often experience psychological distress, frustration, and medical trauma from years of disbelief and neglect. Dr. McGill expands upon this, stating that “warriors share stories that sound like medical trauma that reduce their likelihood of wanting to seek care in the future, but there is little research on medical trauma in SCD.” In order to better treat warriors, there is a call for further research on how to treat SCD pain and how to educate providers on reducing their biases.

As Dr. McGill summarizes, “SCD is complex. There’s not enough research about the stigma faced by warriors. I want to understand how stigma intersects for these warriors to affect their lived experiences.” Stigma can cause many adverse health effects. A systematic review identified four key domains of stigma experienced by individuals with SCD: social consequences, effects on psychological well-being, effects on physiological well-being, and impacts on patient-provider relationships and care-seeking behaviors. Socially, stigma can lead to isolation and strained relationships, as others may misunderstand the nature of the disease. Psychologically, the burden of stigma contributes to increased rates of depression and anxiety among SCD warriors. Physiologically, stress from stigma can exacerbate disease symptoms, leading to more frequent pain episodes. In health care settings, negative perceptions from providers can discourage patients from seeking necessary care, further compromising their health. “Stigma is also linked to worse physical and mental health, worse pain outcomes, poor sleep, increased depressive symptoms, and decreased willingness to seek care,” Dr. McGill adds. Addressing these layers of stigma requires systemic change, including better provider education, increased research funding, and a shift in how pain is understood and treated.

Still, researchers are actively working to reduce the stigma surrounding SCD by improving health care provider education, promoting more inclusive care practices, and advocating for equitable access to treatments. Dr. McGill highlighted that “there is a need for more general education about pain at the clinician level. So many health conditions across specialties experience pain, so it is a priority to increase pain education.” She believes “it’s also important to consider other social determinants of health. For example, individuals with SCD have high unemployment rates. Policies that aim to evaluate patients' resources are important.” SCD is at the center of many significant conversations about stigma and how it intersects to impact a patient’s care experience. While curing any disease is the main goal, there is still a long way to go to ensure patients with SCD are represented and treated fairly in health care settings.